As the summer draws to a close, backyard birders are seeing signs of seasonal change. Find out what birds our members and friends have seen lately in their yards and neighborhoods.

American Crow

American Crow

BY DAVE ZITTIN

The American Crow has to be the most difficult backyard bird to write about because there have been so many interesting studies on this species. The goal of this article is to introduce you to the American Crow and hopefully make you want to learn more on your own.

American Crow. Note the brown feathers. Photo by Tom Grey

When I was a grad student, we spent summers in a small fishing village on the West Coast of Vancouver Island, where we frequently heard a metallic “bong” or “boing” sound similar to that of a rapidly released metal spring. The sound came from within a dense conifer forest, and we spent months looking for its source. Eventually, we found it: a Northwestern Crow. (Recent research has folded the Northwestern Crow into the American Crow, so the Northwestern Crow no longer exists as an independent species.) Crows can mimic sounds of other species including the human voice, so the boing sound we heard could have been a mimic of some unknown sound.

American Crow by Brooke Miller

American Crows are highly-adaptable opportunistic feeders consuming seeds, marine, and terrestrial invertebrates, eggs, nestlings of other bird species, turtles, small rodents, fruit, road-kill, garbage, and more. Once, we had American Crows feast on bags of groceries we were transporting by boat. They quickly found our cheese packages, and during the seconds we were away from the boat carrying bags into the house, they excavated the cheese blocks remaining on the boat. This species is extremely intelligent and will sometimes cooperate when it comes to acquiring food. In one case, American Crows were observed taking a fish from a river otter. One pecked at its tail, causing the otter to drop the fish, while the other crow grabbed the fish and flew off to a perch where they both had a feast. American Crows are often mobbed by other bird species who are protecting their eggs and young from this predator. American Crows will eat carrion, but their beaks aren’t strong and sharp enough to pierce the skin of a dead animal, so they must wait for a better-equipped carrion feeder to break the skin. Crows will also carry turtles, nuts, clams, etc. into the air and drop them on hard surfaces to crack them open.

American Crows congregating by John Scharpen

American Crows are social. Family groups of up to 15 individuals stay together, and sibs from previous hatches help raise younger brothers and sisters. Outside the breeding season, large numbers of American Crows come together to roost at night. These roosts can consist of tens of thousands of individuals and can be quite annoying to nearby people.

American Crows damage some crops. It is legal to hunt and kill this species in some areas of the United States. However, evidence suggests that American Crows may benefit corn crops by eating pest insects that overwinter in the corn stubble.

Crows have an uncanny ability to recognize human faces and will distinguish good people from bad (see behavior video in the explore section).

Attracting Crows to Backyards

I don’t go out of my way to attract them, but they do show up infrequently to eat the bird seed mix I spread on the ground.

Description

A large, black bird with a large black beak, black feet, and black legs. Their feathers have a slight iridescent sheen. The body feathers of molting individuals take on a brown coloring. The Latin species name of the American Crow is brachyrhynchos. Brachyrhynchos is Latin for “short-beaked.” This name is confusing to me because many other members of the same genus, Corvus, have beaks that are as short as the American Crow’s. Compared with the Common Raven (same genus), there is no question that the crow’s beak is shorter. Perhaps this is the reason.

Notice the squared-off tail end of this American Crow. Photo by Vivek Khanzodé

Distribution

The American Crow is found throughout the year over much of the United States, along the west coast of North America, and west into the Aleutian Islands. They also occur across much of southern Canada in the breeding season. They will live almost anywhere there is a food source and some trees on which to nest and perch. They tend to avoid deserts.

Similar Species

The Common Raven and the American Crow are similar at first glance. Paying attention to a few differences can help determine which species you are viewing. In flight, Common Ravens exhibit long glides and can soar in thermals. American Crows exhibit short glides and flap their wings more than Common Ravens. They do not soar in thermals. You will often read that the Common Raven’s tail is wedge or diamond-shaped in flight and the American Crow’s tail lacks this diamond shape. Be careful with this difference because as crows land or fly in a slow, steep turn, they splay their tails, giving them a wedged-shaped appearance.

American Crow in flight by John Scharpen. Note the shorter fan-shaped tail.

Common Raven in flight by John Scharpen. Note the diamond-shaped tail.

American Crows and Common Ravens make different sounds. Typically the adult Raven makes a guttural “gawk” sound, and the adult American Crow usually makes its trademark “caw” sound. A roosting American Crow bobs its head down then up as it vocalizes and sometimes slightly opens its wings. A vocalizing Common Raven is relatively still. The throat and head of the Common Raven are often fluffed or ruffled; those of the American Crow are usually smooth.

Common Raven with fluffed throat and head by Dave Zittin

The Fish Crow of the south and eastern parts of the United States looks very much like the American Crow. They can be told apart by sight and sound.

Explore

To explore American Crows in more detail, I recommend the following videos:

Crow “boing” sound from the Urban Nature Enthusiast. Note the strong bobbing when they vocalize.

Excellent video on American Crow behavior from Lesley the Bird Nerd. Note bobbing while vocalizing at 3:11 and 8:53

Common Raven versus American Crow from the Raven Diaries

More Backyard Bird Information

View more common Santa Clara County Backyard Birds

Visit our Backyard Birding page

Tell us what you’re seeing in your yard! Send your notes, photos, and sound clips to backyardbirds@scvas.org. We’ll feature your submittals on our website.

Banner Photo: Vivek Khanzodé

All Around Town

All Around Town

All Around Town

Brown-headed Cowbird

Brown-headed Cowbird

BY DAVE ZITTIN

GeneralIy I find it unsettling to watch a tiny Dark-eyed Junco feeding a much larger immature Brown-headed Cowbird. The junco in our backyard worked overtime feeding the voracious, constantly begging juvenile cowbird.

Brown-headed Cowbirds are brood parasites. Brood parasites lay their eggs in the nests of other birds of the same or a different species. Brown-headed Cowbirds do not build their own nests, so their eggs are always laid in nests of a different species. Bird biologists call this obligate nest parasitism. The bird receiving the nest parasite’s eggs is called a host.

Brown-headed Cowbird by Teresa Cheng.

The Brown-headed Cowbird is a member of the genus Molothrus which combines two ancient Greek words: “to struggle” and “to sire”. The Brown-head Cowbird is a member of the family Icteridae which includes, among others, blackbirds, orioles, and meadowlarks.

Female Brown-headed Cowbirds are stealthy and spy on the nests of host species. When the time is right, they sneak into the nest and lay their eggs. They sometimes destroy the host’s eggs. The cowbird eggshell is strong, and their eggs have an incubation period that is usually shorter than that of the host eggs. The young cowbird grows faster than the young of the host bird. Young cowbirds often push eggs and the young of the host species out of the nest to reduce competition for food.

Dark-eyed Junco feeding juvenile Brown-headed Cowbird by Sushanta Bhandakar

Before Europeans arrived in the Americas, Brown-headed Cowbirds were limited to the grasslands of central North America where they followed buffalo herds that stirred up insects. The diet of Brown-headed Cowbirds is about 70% grain and 30% insects. They parasitize nests on the edges of forests. Early settlers cleared trees which led to forest fragmentation that allowed them to expand their range by providing more open areas, more forest edges, and more potential host species. By the 1980s, the Brown-headed Cowbird had spread over the entire United States, northern Mexico, and southern Canada. They took advantage of new host species that had no experience with their aggressive nest parasitism, and today they are nest parasites of over 240 bird species.

Dark-eyed Junco feeding two juvenile Brown-headed Cowbirds by Tom Grey

Some host species eject the eggs of nest parasites, bury them by constructing a new nest floor or damage the eggs by breaking their shells. However, some species accept the Brown-headed Cowbird eggs. For some hosts, the situation is dire. A well-studied case is that of the endangered Kirtland's Warbler. Before 1900, Brown-headed Cowbirds had not occurred in the breeding areas of this warbler in Northern Michigan. In 1971, only 200 male Kirtland’s Warblers were known to exist and about 70% of the nests of this warbler were parasitized by cowbirds. Cowbird traps were employed and trapped cowbirds were killed. In 2018, the program was deemed successful, and the traps were removed. There are now estimated to be 2300 breeding Kirtland’s Warbler males and less than 1% of nests are estimated to be parasitized. Today the Cowbird population is greatly reduced in areas where this warbler nests. This is not so much because of trapping, but because forests have been managed to regrow, increasing the ratio of forest area to forest edge. It’s hard to fault the cowbird. It did what it does best and human activities opened the way for it to expand its range. Today it’s recognized that trapping cowbirds and habit restoration have to go hand in hand to rescue an endangered species impacted by nest parasitism from the Brown-headed Cowbird.

Attracting Brown-headed Cowbirds to Backyards

If there are nesting birds in and around your backyard, Brown-headed Cowbirds will likely appear during the breeding season, especially if you have grain feeders. In our backyard, the Brown-headed Cowbird seems to appear a few days per year during the onset of nesting.

Description

Brown-headed Cowbirds are stout blackbirds with a thick, conical bill. Adult males have brown heads and black bodies. Under poor light conditions, the head appears black. Females are light brown with a slightly lighter-colored head, a white throat, and fine streaking on the belly. Juveniles have heavy streaking on their underparts and their backs appear scaly.

Female Brown-headed Cowbird by Tom Grey

Distribution

Brown-headed Cowbirds occur over most of Mexico, the United States, and southern Canada. They are in Santa Clara County throughout the year.

Similar Species

The female Brewer’s Blackbird resembles a female Brown-headed Cowbird. The cowbird has a lighter-colored throat and a shorter, thicker conical bill compared to the longer, thinner bill of the female Brewer’s Blackbird. In general, the thick, conical bill separates the Brown-headed Cowbird from other similarly colored local icterid species. The eye color of the Brown-headed Cowbird is dark, never red or yellow.

Explore

Biology, ecology, and evolution of nest parasitism

Brown-headed Cowbirds

More Backyard Bird Information

View more common Santa Clara County Backyard Birds

Visit our Backyard Birding page

Tell us what you’re seeing in your yard! Send your notes, photos, and sound clips to backyardbirds@scvas.org. We’ll feature your submittals on our website.

Banner Photo: Brown-headed Cowbird by Teresa Cheng

All Around Town

Bushtit

Bushtit

BY DAVE ZITTIN

Bushtits rarely show up in our backyard, but we have seen them a few times over the years. Bushtits are social. They live in flocks of 10 to 40 individuals. When it’s cold, they huddle at night to keep warm. They feed as a flock, gleaning insects and spiders from trees. When one decides to move to another tree, the others follow in an irregular single file line. They take on every imaginable position when feeding, frequently hanging upside down, much like Chestnut-backed Chickadees.

Bushtit by Dave Zittin

Bushtits make a lot of noise, but it can be difficult to hear their ethereal calls on windy days. Their incessant calling keeps the group in touch with each other. The calls are low in volume and are high-pitched squeaky “tsips” and “pits”. To my ears, they sometimes sound like small crystals making a faint tinkling sound as if they are a living wind chime.

Bushtits are the only members of the family Aegithalidae, the long-tailed tits, in North America. The family has 4 genera and 11 species and most occur in Eurasia.

Bushtit by Treasa Hovorka

Bushtits have an unusual, well-camouflaged nest. It resembles a tube sock, about 1 foot in length, and hangs from live or dead branches. There is a hole near the top that allows entry into a narrow tube that widens near the base of the sock-like nest. The nest construction is constructed from vegetative matter, animal hair, and spider webs which give a nest a stretchy quality. It is well insulated and allows the parents to leave the young alone for longer periods than if the nest were open to the elements.

Bushtit and nestling in nest by Janna Pauser.

Bushtits are one of the first birds to be described as having nest helpers. Helpers are not the biological parents but will help the parents build a nest and later help feed the young. Evolutionists study species with helpers to promote understanding of the selective advantages that come to a non-parent in helping a mating pair to raise young. Observation shows that most Bushtit helpers are unmated males or males that have lost a nest. Helpers are not common among west coast Bushtit, but field research has shown almost 40% of active nests in the Chiricahua Mountains of Southeast Arizona have helpers.

Attracting Bushtits to Backyards

Bushtits are not attracted to feeders. They are foliage-gleaners and consume small arthropods found on leaves, petioles, and branches. A brushy or treed yard is the best way to attract Bushtits.

Description

Bushtits are small, mostly gray birds about the size of a Ruby-crowned Kinglet (3-4 inches in length). They have a large head, a rounded body, and a long tail. The beak is small and pointed. The sex of an adult is determined by the color of its iris. Females have irises which are a dull yellow to milky white color. Males have dark irises. Young Bushtits of both sexes have dark eyes. Bushtits in the Pacific region have upper parts that have a brownish wash; those in the interior have white upper parts.

Female Bushtit by Dave Zittin. Note the whitish eyes, rounded head, short beak and long tail.

Male Bushtit by Teresa Cheng. Note the dark iris.

Distribution

Bushtits are found in the western U.S. Their northern limit is in southern British Columbia, and they extend south into Central America. They are not known to migrate long distances, but are constantly in foraging mode, moving from tree to tree searching for food. They do come down from high-altitude areas to avoid the winter cold and during this time they may be found in brushy desert areas.

Similar Species

Nothing looks like a Bushtit in Santa Clara County. In the dry southwest, the young Verdin resembles a Bushtit, but their bills and other features are different. The uniform gray color of the Bushtit, its social nature, and chickadee-like behavior make for easy identification in Santa Clara County.

Explore

More Backyard Bird Information

View more common Santa Clara County Backyard Birds

Visit our Backyard Birding page

Tell us what you’re seeing in your yard! Send your notes, photos, and sound clips to backyardbirds@scvas.org. We’ll feature your submittals on our website.

Banner Photo: Bushtit by Vivek Khanzodé

All Around Town

American Robin

American Robin

by Dave Zittin

We used to see American Robins in our backyard when we had a green lawn. Due to drought conditions, there is no lawn and there are no American Robins.

Robins are members of the thrush family. This family occurs on every continent except Antarctica. Early colonists gave the American Robin its name because it vaguely looks like the unrelated European Robin. The American Robin is the largest thrush in North America. The Western Bluebird and the Hermit Thrush are two other common thrush relatives found in Santa Clara County.

American Robin by Dave Zittin.

Robins adapt well to humans. Their range has expanded due to human activities including parkland development, domestic planting of ornamentals, orchards, and other agricultural activities which tend to promote fruit or increased invertebrate activity at or near the ground.

Ornithologists once thought that American Robins used their auditory senses to find earthworms, but recent research indicates that they use visual cues. Robins stare at the ground with one eye for long periods to find earthworms emerging from the soil. Green lawns mean wet soil and wet soil means earthworms and other invertebrates.

Green lawns also often mean pesticides. Because the American Robin associates with humans, it has become an important indicator of toxic chemicals in the environment.

American Robin by Dave Zittin.

Locally, American Robins are probably the number one carrier of West Nile disease. News accounts give the impression that crows and jays are significant carriers, but research indicates that West Nile is more common in the American Robin. And while West Nile is almost always lethal to crows and jays, robins are able to carry the disease with fewer ill effects. A mosquito species spreads the disease to birds and humans. This mosquito takes blood meals from roosting American Robins and robins then serve as an amplification mechanism enabling more mosquitos to acquire the virus and eventually infect people. It’s not the robin’s fault: it’s the virus-mosquito combination that is the culprit.

American Robins have a high mortality rate; only 25% of fledged American Robins make it through November of the year they were hatched. Even though there are records of Robins older than 12 years, research shows that nearly 100% of a year cohort dies in 6 years.

Attracting American Robins to Backyards

Fruiting plants provide an important early source of nutrition for immature robins, which are less experienced at foraging for invertebrates.

Cornell claims that American Robins are attracted to feeders, but I have yet to see one on either our suet feeder or grain feeder.

American Robin by Tom Grey.

Description

American Robins are easy to identify. The male has a black head, a yellow bill, a striped throat, a broken white eye ring, and a distinct rufous colored breast. The female looks similar but tends to have duller colors. Immature male American Robins resemble females. Juveniles are heavily spotted to a point of having a mottled appearance and are often confusing to beginning birders.

Juvenile American Robin by Brooke Miller. Note the mottled appearance.

Distribution

With a few exceptions, American Robins occur everywhere in the U.S. and northern Mexico. They are in Santa Clara County all year. Based on eBird frequency charts, they are least abundant in the county in the summer and fall.

Migration is complicated. Some individuals don’t wander far from their breeding territories. This is especially the case where climates are mild and food is available in the winter. Important factors that influence migration are the availability of ground invertebrates in the spring and edible fruit in the fall and winter. That said, many do migrate from Mexico and the southern United States to the Canadian-U.S. border and north to the Arctic Ocean during summer breeding season.

During fall and winter, robins typically roost in large flocks and spend more time in trees where edible fruit occurs. A few years ago we were birding in Florida in the winter when we came across a large leafless tree in which there were more than 200 American Robins. To date, I have not seen anything like this in Santa Clara County.

Similar Species

Nothing in Santa Clara County looks like an American Robin. The Spotted Towhee has similar rufous coloration on its flanks, but its breast is white, not rufous, and this towhee lacks a white eye ring.

The American Robin’s song contains sounds that swing upward, often sounding like “cheer-up”. They have different calls, but a common one sounds like a high-pitched whinny. The Black-headed Grosbeak’s song is similar but has segments that go down sounding like a child’s sliding whistle, and usually contains distinct short-bursts of trills that the robin lacks.

Explore

The song of the Black-headed Grosbeak - note pitch slides and trills

More Backyard Bird Information

View more common Santa Clara County Backyard Birds

Visit our Backyard Birding page

Tell us what you’re seeing in your yard! Send your notes, photos, and sound clips to backyardbirds@scvas.org. We’ll feature your submittals on our website.

Banner Photo: American Robin by Hita Bambhania-Modha

All Around Town

Lesser Goldfinch

Lesser Goldfinch

Dave Zittin

Lesser Goldfinches are regular visitors to our backyard. Most of the time this tiny finch is seen in mixed flocks, shoulder-to-shoulder at the seed feeder with Oak Titmouse, Chestnut-backed Chickadee, and their finch relatives, the Pine Siskin and House Finch.

Male Lesser Goldfinch. Note the black crown extending to the nape. The white rectangle on the wing shows most of the time, but not always. David Zittin

Lesser Goldfinch live almost entirely on seeds. Sunflower and niger seeds are among their favorites. In nature, they feed on flowering plants, especially those in the composite family, and are often seen eating on the common fiddleneck (Amsinckia spp.). Lesser Goldfinches are one of the few species in North America that rear their young exclusively on seeds.

Female Lesser Goldfinch. Note the prominent white rectangular area on the base of the outer primaries. Because there is no black crown, this is a female. Hita Bambhania-Modha

Lesser Goldfinches are acrobats and a lot of fun to watch when feeding in the wild. They are light enough to hang onto wispy flower stalks and can consume seeds upright, upside down, and in any other position you can imagine. When bullied by other birds at our seed feeder, it is not uncommon to see one go upside down on the feeder’s perch wires in order to yield to a more aggressive bird.

The Lesser Goldfinch, Spinus psaltria, is a member of the finch family, Fringillidae, which includes 49 genera and 229 species. In the genus Spinus there are 20 species, four of which occur in the United States: Lawrence’s Goldfinch, Pine Siskin, American Goldfinch, and Lesser Goldfinch. A few species are Eurasian and the rest occur in Latin America.

Black-backed Lesser Goldfinch in Costa Rica. Note the white rectangle on the wings and yellow under tail coverts. Dave Zittin

The Lesser Goldfinch shows different colors over its distribution. In our area, they have yellow-greenish backs. Individuals east of the Rockies and south into Latin America have darker upperparts, with backs becoming blacker the further south one goes into Mexico. In Costa Rica once, I was sure I had a lifer until a local bird expert assured me I was looking at a Lesser Goldfinch. Unlike the American Goldfinch, the colors of the Lesser Goldfinch do not vary much seasonally.

Attracting Lesser Goldfinch to Backyards

The Lesser Goldfinch prefers hanging feeders, but I have observed them feeding off of the ground. They devour sunflower and niger seeds. Provide them with these oily seeds, and they will come.

Description

The Lesser Goldfinch is the smallest of the finches found in Santa Clara County. The male has a black crown that ranges from the upper beak and over the forehead and ends just above the nape (the back of the neck). Both sexes have a white patch at the base of their primaries. When perched, this white base regularly appears as a small white rectangle, but sometimes it is inconspicuous. The adult male also has a white patch at the base of its primaries. When perched, this white base often appears as a small white rectangle, but sometimes it is inconspicuous.

Distribution

Lesser Goldfinches are on the west coast of the U.S. all year. Their northern limit is southwest Washington. They occur in much of Mexico, Central America, and various areas in northern South America. During breeding season some migrate into Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico. The migrations of this species have not been well studied.

Similar Species

The two local species that look somewhat alike are the American Goldfinch and Lawrence’s Goldfinch. The Pine Siskin has a similar body and beak shape, but it has conspicuous streaking on its lower parts, something that the other three Spinus species lack.

The belly of Lawrence’s Goldfinch is gray. The belly of the male Lesser Goldfinch is yellow and pale yellow-green on females and juveniles. Lawrence's Goldfinch has yellow wing bars and the wing bars of the Lesser Goldfinch are white. Also, recall that Lesser Goldfinches have white outer primaries which usually form a visible, small white rectangle on the wing, a feature that the other Spinus species do not have.

Male American Goldfinch. Note that the black cap ends at the top of the head and the white under-tail coverts. Dave Zittin

The breeding American Goldfinch male has a bright yellow, not olive-yellow back and a black crown ends at the top of the head rather than extending over the head and down to the nape. The females of the Lesser Goldfinch and the American Goldfinch look similar, but the Lesser Goldfinch female has indistinct wing bars and the under-tail coverts are typically yellowish. The American Goldfinch female has darker colored wings with obvious wing bars and its under-tail coverts are white.

Explore

Photos of west coast Lesser Goldfinches:

Male Lesser Goldfinch showing black crown extending onto nape. Note white rectangle on the primaries.

Female Lesser Goldfinch. Note yellow under-tail coverts and white rectangle on the primaries.

Photos of American Goldfinch and Lawrence’s Goldfinch for comparison:

Female American Goldfinch. Note white under-tail coverts, prominent white wing bars and brownish back.

Female Lawrence’s Goldfinch. Note yellow-gray wing bars and yellow-edged primaries.

Male Lawrence’s Goldfinch. Note black face, yellow wing bars, and yellow-edged primaries.

Sounds:

The Lesser Goldfinch has various songs and calls, but here is one call I often hear in Santa Clara County. Note the plaintive whistle quality.

Allaboutbirds.org has additional Lesser Goldfinch sounds.

More Backyard Bird Information

View more common Santa Clara County Backyard Birds

Visit our Backyard Birding page

Read our Notes and Tips from a Backyard Birder series

Tell us what you’re seeing in your yard! Send your notes, photos, and sound clips to backyardbirds@scvas.org. We’ll feature your submittals on our website.

Banner Photo: Lesser Goldfinch by Hita Bambhania-Modha

THE GBBC IS HERE!

The Great Backyard Bird Count is happening now, February 18 through 21. Count birds in your yard, neighborhood, or favorite birding spot, and share your observations with scientists. Be part of a global event, join in the fun!

All Around Town

California Scrub-Jay

California Scrub-Jay

by Dave Zittin

California Scrub-Jays are noisy birds and their "weep" call is a common element of the local soundscape, especially in oak and scrub habitats.

California Scrub-Jays are bold and confident around humans. My first close encounter with the California Scrub-Jay occurred many years ago during lunch breaks when I worked in Palo Alto. When we ate outside, employees threw crumbs out to a “resident” California Scrub-Jay, and over time, I got the bird to come closer by reducing the toss distance. After a few weeks, I had the jay landing in my hand and feeding. The two of us saw eye-to-eye: he got food and I got really close looks. I later learned that hand-feeding can be detrimental to some species such as the friendly, but endangered Florida Scrub-Jay. Hand-feeding of this species can cause them to raise young too early in the season. Doing so can reduce the chances of supplying naturally available food during the growing period of the young.

California Scrub-Jay with acorn. Steve Zamek

California Scrub-Jays are members of the New World genus Aphelocoma, of which there are seven species. The name translates to “simple hair” which reflects their feather colors that have no stripes or banding. California Scrub-Jays are a member of the family Corvidae, which also includes crows, ravens, magpies, and Clark’s Nutcracker. Frequently, people call the scrub jay a “blue jay”. This is incorrect because scrub jays are in a different genus than the Blue Jay, which is in the genus Cyanocitta. There are two species in this New World genus; the east coast Blue Jay and the Steller's Jay.

California Scrub-Jays are fairly common in my backyard, but they do not show up every day. They eat grain spread on the ground and when there is no feed on the ground, they eat suet from our hanging feeder.

In nature, a primary food source for this species is acorns. California Scrub-Jays possess an outstanding ability to cache food and use spatial memory to find it later, much like their cousins, Clark’s Nutcracker. Of course, they don’t find it all, and there is some speculation that they are instrumental in facilitating the spread of various oak species. California Scrub-Jays also eats insects, reptiles, and small mammals. One time when driving near Loma Prieta Saddle we saw a California Scrub-Jay trying to kill a young rabbit in the middle of the road. Fortunately for the rabbit and to the detriment of the jay, I stopped, which kept the bird away until the bunny could make it across the road and into the brush while I got an earful from the jay.

California Scrub-Jay by Treasa Hovorka

California Scrub-Jays are aggressive and dangerous to smaller birds such as crowned sparrows, which keep a radius of a few yards when a jay is present.

Some jay species, for example, the Florida Scrub-Jay, are known for cooperative breeding, which is the rearing of young by individuals other than their parents. Western scrub jay species, including the California Scrub-Jay, do not demonstrate cooperative breeding.

The calls made by the California Scrub-Jay are varied, but a common call heard locally is a "weep" with an upswing in pitch.

California Scrub-Jays will vigorously mob bobcats, house cats, squirrels, owls, and anything else they think is a threat to them. The racket from this mobbing is noisy and can sometimes lead a birder to good views of a raptor such as an owl or a hawk.

California Scrub-Jays are excellent at recognizing and tossing the eggs of brood parasites (species that lay their eggs in the nests of non-related species) out of their nest. Researchers have experimentally added cowbird eggs to jay nests and observed they were tossed overboard in short order. This means that brood parasitism is virtually nonexistent for this species.

Attracting California Scrub-Jays to Backyards

Spreading seed on the ground and suet feeders may draw California Scrub-Jays to your backyard. Sometimes they will also perch on our cylindrical, hanging seed feeder, but this is awkward for them and I don’t see this often.

Description

A medium-sized, crestless and long-tailed bird. Adults can be easily recognized by a gray-brown back with otherwise dull blue upper parts. The under parts are dull-whitish. Other features include dusky-colored ear coverts, a prominent whitish supercilium (eyebrow), and two bands of dark-bluish streaks extending onto the sides of the upper breast, almost forming a necklace. The beak, legs, and feet are black. The blue plumage tends to be duller blue in the Pacific Northwest, becoming darker and more purple towards southwestern California. Adults show no pronounced plumage differences between sexes. Juveniles have a lot of sooty gray color and lack the blue on top of their heads.

Scrub-Jay showing its gray back, blue wings and head, and conspicuous white eyebrow. Carter Gasiorowski

Distribution

California Scrub-Jays are a common year-round resident of the western coastal states, extending from Northern Washington to the tip of Southern Baja California. They are not migratory but tend to wander from their breeding range in the winter.

Similar Species

Nothing in our area looks like a California Scrub-Jay. Learning to tell their call from the Steller’s Jay takes a little practice. The flatter pitched call of Steller’s Jay often confuses beginning birders, but with a little experience, they are easy to tell apart.

Explore

Juvenile California Scrub-Jay

Typical “weep call” of California Scrub-Jay with pitch upswing

Flatter, screechier call of Steller’s Jay for comparison

More Backyard Bird Information

View more common Santa Clara County Backyard Birds

Visit our Backyard Birding page

Read our Notes and Tips from a Backyard Birder series

Tell us what you’re seeing in your yard! Send your notes, photos, and sound clips to backyardbirds@scvas.org. We’ll feature your submittals on our website.

Banner Photo: California Scrub-Jay by Brooke Miller

All Around Town

Feisty kinglets, hungry hawks, and a charm of hummingbirds! This special edition of All Around Town includes your latest observations, plus your favorite backyard birding moments of 2021.

Cedar Waxwing

Cedar Waxwing

by Dave Zittin

We know it is winter at our place when flocks of Cedar Waxwings appear from time to time on our black walnut tree. Frequently we will see more than 25 Cedar Waxwings at a time high on the tree, doing their whistle call and looking very much like tree ornaments.

There are only three waxwing species in the world: The Cedar Waxwing, the Bohemian Waxwing, and the Japanese Waxwing. Waxwings are in the family Bombycillidae (bombux=silk). Their closest cousins are the silky flycatchers, in the family Ptilogonatidae which includes the Phainopepla. Both families are fruit eaters and have smooth outer feathers that give them a silky appearance.

Notice the black face surrounded by a thin white line, the yellow-tipped tail and the yellow belly. Photo by Erica Fleniken.

Cedar Waxwings and Bohemian Waxwings are the most prominent fruit-eating birds in North America. They have digestive system adaptations that enable them to thrive on sugary fruits. Cedar Waxwings are the only species outside the tropics to feed fruit to their young. As an interesting aside, the young of the brood parasite (a brood parasite lays its eggs in other birds' nests), the Brown-headed Cowbird, often die in Cedar Waxwing nests because they are unable to survive on fruits fed to them by adult Cedar Waxwings.

Cedar Waxwings consume the berries from numerous plant species. The distribution of North American Cedar Waxwing populations have grown due to human activities that include planting berry-producing ornamentals, orchard expansion, and allowing farmlands to revert to natural states. Cedar Waxwings have a mutualistic role in contributing to the success of the plants whose berries they eat by spreading seeds in their excrement.

Cedar Waxwings eat berries whole. Smooth outer feathers give these birds a silky appearance. Photo by Steve Patt.

Cedar Waxwings are especially susceptible to death from alcohol consumption that comes with eating fermented fruits. They are often killed from falls or flying into objects when intoxicated. The death of large portions of flocks from alcohol consumption has been noted in the literature.

Flocks of Cedar Waxwings raid fruit crops that are defended by other species. Species such as the Northern Mockingbird and the American Robin aggressively guard prized winter fruit crops. Robins can defend their fruit crop against fifteen or fewer Cedar Waxwings, but when the Cedar Waxwing flock exceeds 30 or more birds, the robin is helpless to stop the raid. In one case, Cedar Waxwings cleared a crab apple crop in 25 minutes when 36 birds descended on a tree defended by a robin. Although I have not encountered information on predation reduction due to flocking, I would not be surprised if this is also a factor. Raptors such as the Sharp-shinned Hawk, Cooper’s Hawk, and Merlins kill and eat Cedar Waxwings. Flocking tends to confuse predators, leading to reduced predation rates.

Cedar Waxwing and American Robin squabbling over a feeding territory by Erica Fleniken.

Cedar Waxwings rear their young in the late summer when the availability of ripe fruit is at a maximum. For the first few days, the brood receives a protein-rich diet of insects in their diet brought to them by the father, but this soon ends, and fruits become their primary food source. After the breeding season, when the young have fledged, Cedar Waxwings flock and feed on tree sap, cedar berries, fruits of mistletoe, toyon, madrone, cultivated berries, etc. Insects also supplement their diet.

Attracting Cedar Waxwings to Backyards

If you want to see more of this species in your backyard, consider planting shrubs that produce berries that they eat during the winter. See the “Birds And Blooms” link below for more information. Cedar Waxwings are susceptible to window collisions, so do whatever it takes to prevent this from occurring.

Cedar Waxwing flock bathing by Hita Bambhania-Modha.

Description

Cedar Waxwings can be identified by their striking black masks with a thin, white surrounding outline, a crested head, red wax-like endings of the secondary feathers, and the striking yellow ends of the tail feathers. The number of red-tipped secondary feathers increases with age, and some ornithologists have suggested that the higher the count of these red tips, the more attractive an individual is as a mate.

Cedar Waxwing showing 6 red-tipped secondaries, a yellow-tipped tail and its face mask by Dave Zittin.

Cedar Waxwings do not have a song, but they do have a very high-pitched whistle-like call.

Distribution

In the summer, breeding populations of the Cedar Waxwing occur across the most northern U.S. states and extend north, almost to the Arctic Circle.

In the winter, they migrate south and occur from the Canadian border south into northern Central America. During the winter, they form nomadic flocks, often seen in Santa Clara County. Their highest winter densities occur in the southeastern plains of Texas, where they feast on juniper berries.

Similar Species

The Bohemian Waxwing is the only bird on the North American Continent that looks similar to the Cedar Waxwing, but they have a more northern distribution and are rarely seen in California. Among other differences, Bohemian Waxwings have two white rectangles on their wings that Cedar Waxwings lack.

Explore

An excellent video that pretty much says it all about this species: Cornell Lab of Ornithology Video on Cedar Waxwings

Note how a pair of birds passes a food particle back and forth during courtship: Video of Cedar Waxwings courting

Hints on attracting them to your backyard from “Birds and Blooms” https://www.birdsandblooms.com/birding/attracting-birds/attract-waxwings-berries/

Listen to the high-pitched “seee” call of the Cedar Waxwing: https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/cedar-waxwing

Distribution map: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Cedar_Waxwing/maps-range

More Backyard Bird Information

View more common Santa Clara County Backyard Birds

Visit our Backyard Birding page

Tell us what you’re seeing in your yard! Send your notes, photos, and sound clips to backyardbirds@scvas.org. We’ll feature your submittals on our website.

Banner Photo: Cedar Waxwing by Brooke Miller

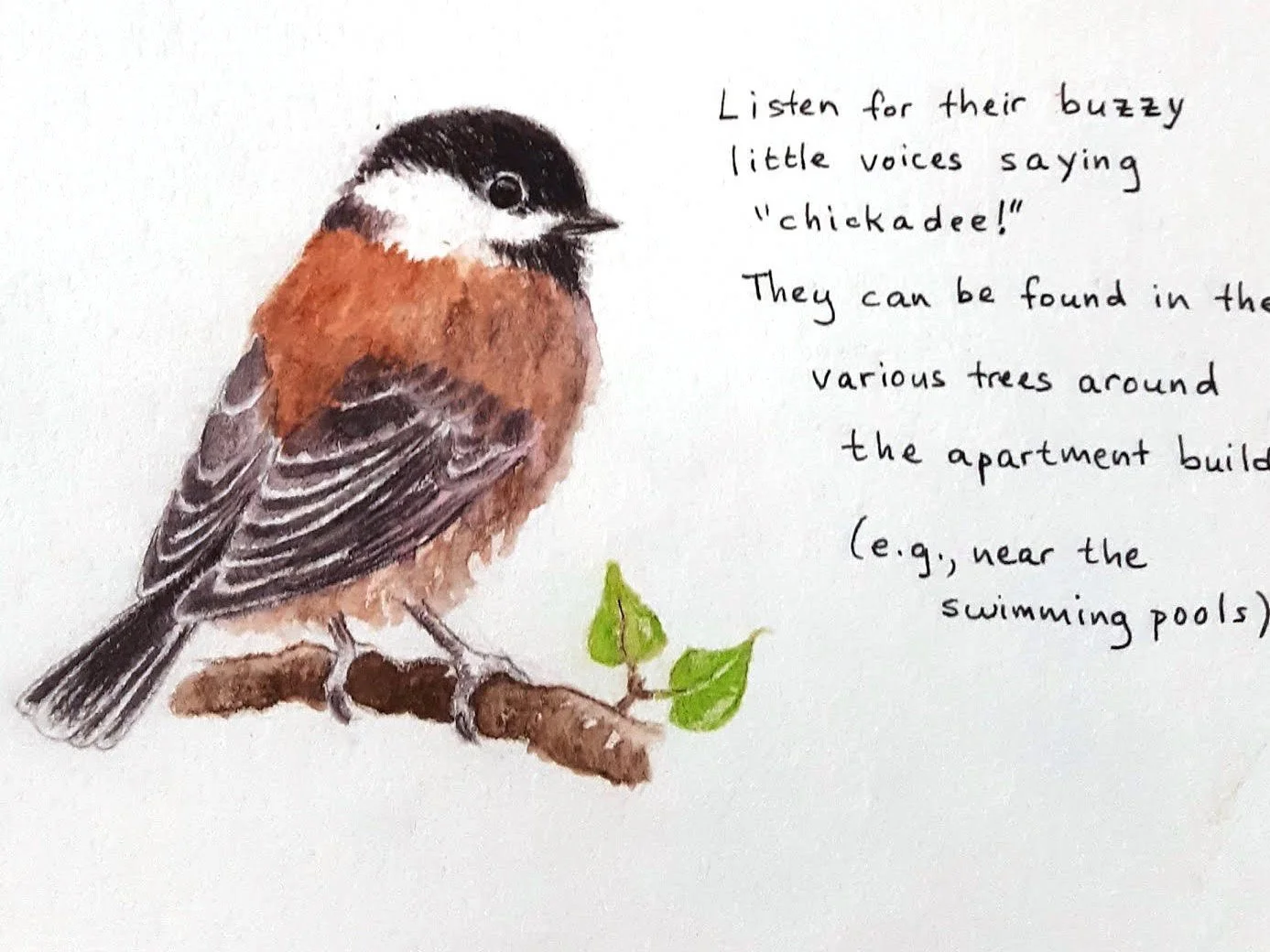

GETTING TO KNOW THE NEIGHBORS

New to the Bay Area, SCVAS Member Francesca Ricci-Tam set out to meet and document the birds near her home. Enjoy Francesca’s sketches and stories of her avian neighbors in our nature art gallery. How many of these birds live near you too?

All Around Town

Black Phoebe

Black Phoebe

by Dave Zittin

Someone pointed out that more Santa Clara County eBird lists have Anna’s Hummingbird than any other species. I guess, but it would not surprise me if the Black Phoebe is as high on the list of frequently observed species. Examining my data, it occurs on about a third of my county eBird lists.

Black Phoebes are in the genus Sayornis with two other species: Say’s Phoebe and the Eastern Phoebe. The French naturalist Charles Lucien Bonaparte, coined the genus name, Sayornis, which translates to Say+bird in honor of Thomas Say, an American entomologist, conchologist, and herpetologist.

Black Phoebe by Dave Zittin.

Phoebes are tyrant flycatchers (family Tyrannidae) of which there are more than 400 species.

Black Phoebes are territorial, monogamous and pairing may last for up to five years.

Attracting Black Phoebes to Backyards

You cannot do much to attract the Black Phoebe to your backyard, although sometimes they are attracted to mealworms. They are wait-and-sally flycatchers, usually waiting on low perches for an insect to come into view and then flying out, grabbing it and returning to the same perch.

A few times a year, one perches in our backyard to forage for insects. Our neighbor used to have a green lawn with a lot of crane flies, and a resident Black Phoebe would swoop down from perches on posts and trees to capture insects on his lawn throughout the summer.

Black Phoebes require a source of mud for nest building and a nearby source may attract them to nest on your property.

Description

No other bird in Santa Clara County looks like a Black Phoebe. This dapper flycatcher has mostly dark sooty-gray upperparts and a white belly ending at the upper breast with an inverted ‘V’ surrounded by a sooty-colored throat area. The under-tail coverts are also white. Black Phoebes have a large, squarish head that frequently shows a peak.

Adult Black Phoebe by Dave Zittin

Adult Black Phoebe feeding juvenile. Note the reddish-brown feather tips on the back of the young bird. Photo by Brooke Miller.

Juveniles have reddish-brown edges on various feathers on their backs, but the red-brown color is conspicuous on the edges of the wing coverts.

Black Phoebes pump their tails while roosting. This is characteristic of the genus Sayornis.

Distribution

Black Phoebes have an extensive range. Their northern breeding limit is Southern Oregon, and their range extends south for thousands of miles into Argentina. They occur along the entire length of California, from the coast and east to the western slopes of the Cascade and Sierra Nevada Mountains and south into Baja California along with the coast range.

Black Phoebes in our area more or less stay in the same place throughout the year.

Local distribution is determined by the availability of suitable nesting conditions. As mentioned earlier, they require mud for nest building, and are therefore associated with wet or damp areas. They build their mud-plant fiber nests on vertical walls within a few inches of a protective ceiling to shield the young from sun and inclement weather, to reduce access by predators, and possibly reduce brood parasitism by other species. Nest areas include rock faces, bridges, and the eaves of buildings. Black Phoebes have a strong tendency to reuse old nests

Similar Species

Except for rare sightings of the Eastern Phoebe, there is nothing in Santa Clara County that looks like a Black Phoebe. The sooty-black upper parts, the peaked head, the white undertail coverts, and the white belly make this an easy-to-identify bird in our county throughout the year. Its congenator, the Say’s Phoebe, a winter bird in our county, has an orangish-cinnamon-colored breast and a brownish-colored back.

Explore

The song of the Black Phoebe sounds like repeated tee-hee, tee-hee. With a little imagination, you may hear fee-bee, fee-bee. The Black Phoebe frequently pumps its tail and calls while roosting as it awaits a bug to come into view. Listen to and the typical song and call.

Photo of juvenile Black Phoebe with rusty-red-tipped feathers

For a bonus, listen to the “fee-bee” song of the Eastern Phoebe. The sound of this song eventually became Phoebe, a woman’s name. Listen to the song of the Eastern Phoebe.

More Backyard Bird Information

View more common Santa Clara County Backyard Birds

Visit our Backyard Birding page

Read our Notes and Tips from a Backyard Birder series

Tell us what you’re seeing in your yard! Send your notes, photos, and sound clips to backyardbirds@scvas.org. We’ll feature your submittals on our website.

Banner Photo: Black Phoebe by Tom Grey